🧑🏻 Michael Zhao

Year of Wonders

by Michael Zhao

Year of Wonders: 1665 - 1667

In 1665, Isaac Newton left Cambridge to the English countryside to escape the bubonic plague. Since formal education ceased during his quarantine, Newton was freed from the shackles of a rigorous university curriculum and finally had the space to dive into subjects that fascinated him. What did he accomplish in this two-year period? He ended up developing theories on calculus, optics, and laws of motion and gravity (Newton witnessed the apple fall from the tree outside his chamber window during this period). According to Newton, this period was one of the most intellectual fruitful of his life:

“For in those days I was in the prime of my age for invention & minded Mathematics & philosophy more than at any time since.”

Newton observed the apple falling from the tree from the top right window.

Newton observed the apple falling from the tree from the top right window.

Stories like this are inspiring and useful. If you look at Newton’s innovation as a process: what were the inputs? And what bottlenecks were removed? Understanding the optimal presence/absence of certain elements in the innovation system is useful not just for individuals, but especially for organizations. Maybe it comes down to 4 things: 1. cultivating learning, 2. not stifling motivation, 3. encouraging emergent experimentation 4. giving more space.

Attention is everything

While I wish I could say that I discovered another law of the universe during quarantine in COVID, I admit that my level of curiosity is nowhere close to Newton’s level. I’ve definitely consumed a lot of videos and spent hours on social media. I think more about video games than I do about calculus. I laugh more at memes than I do reading and writing. But having a combination of more alone time + white-collar job has given me space to think more thoroughly about the things that drive me. Quarantine has also given me an opportunity to experiment and internalize ideas that I read about, but never had the environment to think deeply about.

I’ve realized where you place attention determines a lot. Prior to quarantine, most of my attention was centered around work and friends. This probably encompassed 70% of my waking hours. As result, I became better at my job and was able to develop stronger bonds with my friends through in-person interactions. When quarantine hit, there was significantly more time had to myself, and while my attention was briefly focused on consuming more TV, my attention eventually turned inward.

Blas says it best when discussing his years after college in his essay “The Infinite Game”:

“This transition left me feeling unsure of who I was or what I wanted to do, and this led to a lot of wasted time and unnecessary stress. I went out too much, neglected loved ones, and wasn’t building towards anything with any lasting meaning. Don’t get me wrong, it was definitely fun not having practice, tournaments, and pressure for a bit, but it quickly became hollow and I knew things had to change. I eventually faced this hollow feeling by sitting down, for hours at a time, to think through all these nagging questions in the back of my mind.

It was difficult and frustrating, but I made it a priority to get to know myself and self-reflect. I asked myself, “What type of person do I want to become? What do I truly care about? What are my values? What do I want to achieve? What do I enjoy? What do I want to avoid? What types of people do I want to surround myself with? Who do I want as a mentor to learn from and model myself after?” Maybe some people do this at a much younger age, but I hadn’t. I also didn’t want to make any assumptions, so I questioned everything.

While slow and often frustrating, this process is so worth it because it can act as your north star, helping you course correct if you veer off track.”

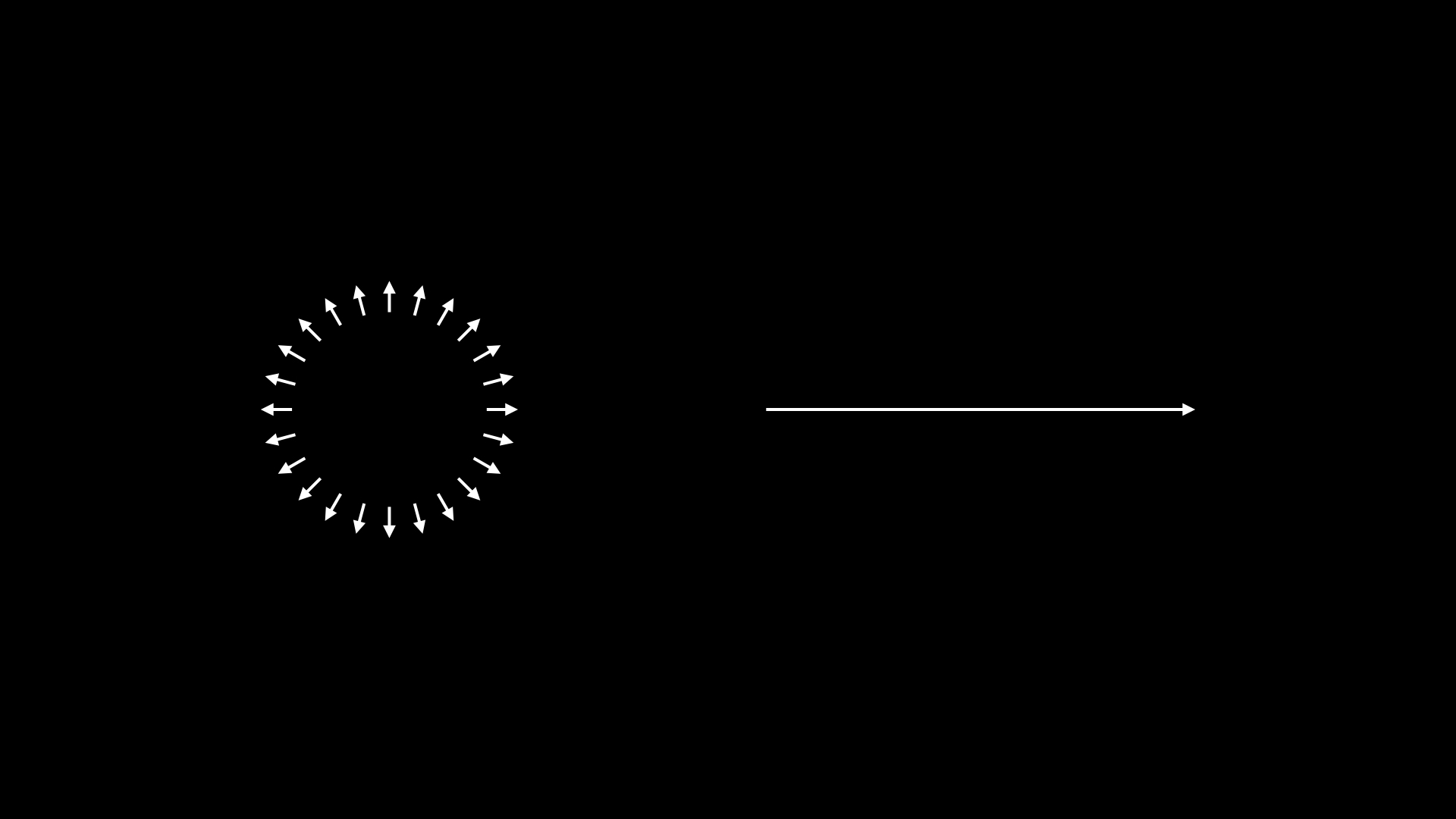

@visualizevalue

@visualizevalue

More alone time forced me to ask those questions - because up until that point, I hadn’t examined myself that deeply. It was during this period I started trying to answer these questions, that I realized that these were very hard to answer. After almost a year of contemplation, I still don’t think I have solid answers to any of these questions.

While I periodically review these questions, I’ve committed to a strategy of actively moving towards skills that I find interesting and useful, and committing to systems that iterate and improve on these skills. The reason I’ve shifted attention towards developing skills rather than changing careers is because I believe career enjoyment is dependent more on external factors. “Meaningful work” that comes from a salaried career feels more like a function of the people and environment you surround yourself with rather than the actual job itself (while it’s probably different for start-ups). In addition, I think the idea of expanding your career moat through disparate skills makes you an antifragile participant in the labor force.

Committing myself to writing every week was a response to explicitly work on my coherence and record phases of my life. Committing myself to programming daily was initially because I wanted to diligence the software companies I invested in, but ended up being more so a tool to automate parts of my job. I continue to read and learn as much as I can about other people’s stories, what they’ve dealt with, how they see the world to internalize as many different frameworks as possible. I am hoping that borrowing these frameworks and through the process of learning, I will slowly iterate my way to better answers to these questions.

Definite Optimism

Something that has started to make me wince is when people have broad/optimistic goals, but can’t answer what specifically they are doing to accomplish those goals. I have been guilty of doing this myself, where I would set a very vague goal (like “be a better person! <3”), smile, and forget about it. At the end of the day, that’s just false mental stimulation - you feel as if you accomplished something, but in reality all you’ve done is state a goal and forgotten about it. Years later you’ll remember the goal, and fool yourself that you have improved based on anecdotal evidence, and perhaps maybe lazily meander on to another vague goal.

That is an example of indefinite optimism - where you are optimistic, but you fool yourself into goals that aren’t actionable and can’t be measured. Beyond the dopamine rush of repeating the goal, it isn’t all that useful. There’s a great quote by Dostoevsky in the Brothers Karamazov:

“Above all, don’t lie to yourself. The man who lies to himself and listens to his own lie comes to a point that he cannot distinguish the truth within him, or around him, and so loses all respect for himself and for others. And having no respect he ceases to love.”

Maybe it’s a bit dramatic, but captures my frustrations with indefinite optimism - the question of “have I improved” is intentionally hazy.

You need goals, and they can be broad. However, they need to be broken down into smaller pieces. If “I want to be a better person” is the broad goal, “eating at least 3 salads a week” and “calling my parents at least once a month” are discrete steps that will move you toward that goal. It’s easy to track the small steps and sum them up when evaluating your performance. This is thinking and doing on a low level, because implementation and execution of the tasks become paramount. This is also definite optimism. Using a definite optimism framework, progress becomes more transparent the smaller the steps you take.

Do what works

2020 was a year of experimentation due to a significant external change. Everything that I’ve written is me looking backwards and piecing together the parts of my approach that I think worked well. Beyond gradual iteration and definite optimism, other ideas that I’ve found to be formative include:

- Life is a fight against entropy

- Life is project management

- Health and curiosity go a long way

- Quantity → quality

As the world adjusts, I will continue to commit time to learning skills and reflecting on this blog and my website. Onwards and upwards.

tags: year - of - wonders, - newton, - quarantine